This piece began as a lengthy comment responding to Ken Parish’s post on my proposal for a third ‘people’s chamber’ chosen by lottery. I posted it on Substack a few weeks ago, but thought it might be a worthwhile post here.

I don’t support citizens’ juries as some kind of ‘hack’ to the existing system, which I see as in an advanced state of decay. That’s because, in the West in the last 800 odd years, there have been two different ‘logics’ applied to the democratisation of monarchy. The first was Magna Carta and the idea of entangling the judgement of one’s peers into the processes of government. And the second was the idea of applying ‘checks and balances’ to government from the 17th century on.

In the former case, an institution was (eventually) developed that husbanded the life world of the people within the machinery of government. In the latter case, the idea of checks and balances was a fine one. But the entire system was administered by the same elite class that it was supposed to hold to account. And that’s turning into an unaccountability machine (see Robodebt, the NACC and the rising tide of careerism in public life to say nothing of the unaccountability machine in the wider governmental structures in business).

In government these checks and balances are mostly, comically easy to subvert – you just win government and appoint your cronies. We’re seeing this in the US and they have more checks and balances than us – like Senate confirmation hearings. Once the partisanship reaches a certain level, things can move very fast.

We might have democratised monarchies by doing something similar to Magna Carta in the legislative and executive branches. But it’s a simple fact of history that we didn’t. But we can get glimpses of what that might look like by looking around. Belgium now has parliamentary committees with 15 elected legislators and 45 randomly selected citizens. There are standing citizen councils in East Belgium, Paris and a few other places.

Michigan has the Independent Citizens’ Redistricting Commission, which draws electoral boundaries. And it does it in a way that is much less corruptible than almost all the systems used elsewhere, including here. These are the kinds of institutions we should be developing. Elsewhere in the Western world, these kinds of things are easily subverted by doing what Scott Morrison did with the AAT. Appointing your cronies to ‘independent’ positions.

If that’s the ‘bulwark against tyranny’ argument, there’s also the ‘can we please have a sensible conversation’ argument. Even where there’s a strong cross-bench, MPs can’t remain MPs without a good deal of double talk. I was discussing budget repair with an independent member of the Tasmanian parliament the other day and they’re almost as hamstrung as party politicians. Because if you want to get elected, your ‘messaging’ though our marvellously dystopian mass and social media has to be pretty reductive. You have to spin your question begging nonsense for media management reasons. Taxes are bad and spending is good! And we wonder why fiscal responsibility is a growing problem!

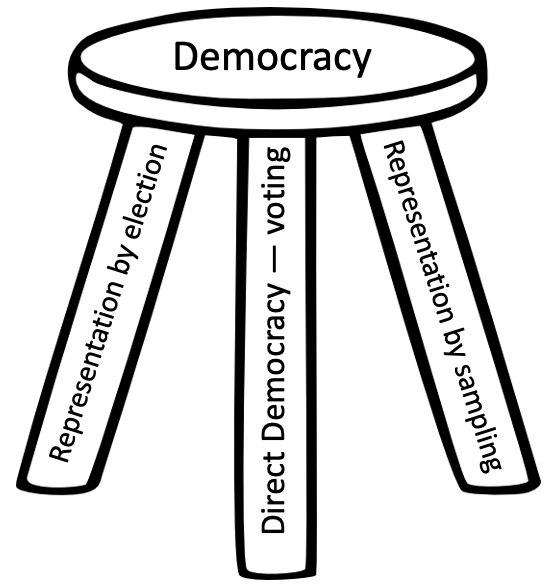

You might ask why don’t I want to abolish the existing system and just back sortition based citizen assemblies.

Two reasons Continue reading →